By Justin Wilder, Owner of Wild Water Plumbing | French Drains

BLUF (Bottom Line Upfront)

I live and work in Onslow County, North Carolina, and I’ve seen firsthand that standing water in your yard is more than just a nuisance – it’s actively damaging your property. Our coastal plain region gets torrential rainfall (Jacksonville, NC averages ~56 inches a year versus the U.S. average of 38 inches), and a single hurricane can dump three feet of rain in a single event (Hurricane Florence dropped ~34 inches near Swansboro in 2018). When all that water has nowhere to go, it destroys septic drain fields, weakens home foundations, and breeds mold and mosquitoes. Simply put, without proper yard drainage, such as a French drain, homeowners across Onslow, Pender, New Hanover, and Carteret Counties risk septic system failure, foundation cracks, erosion, decreased property value, and even health hazards from mildew and pests. I’m Justin Wilder, a Master Plumber and owner of Wild Water Plumbing + Septic, and in this guide, I’ll explain in plain language why every homeowner in our area needs to manage yard drainage before it’s too late, and how a professionally installed French drain can save you thousands of dollars in the long run.

Table of Contents

Introduction – Why Coastal Carolina Yards Turn Into Swamps

Hey, this is Justin with Wild Water Plumbing + Septic. If you live in Onslow County or the surrounding coastal Carolina region, you already know that water has a mind of its own around here. One good downpour or tropical storm can turn a flat, grassy yard into a shallow pond overnight. In some neighborhoods, it feels like the ground never really dries out. Puddles linger for days, grass turns to muck, and that “squish” under your feet becomes all too familiar.

But a soggy lawn isn’t just an eyesore or an inconvenience – it’s a warning sign. As a plumber and septic specialist, I’ve learned that when your yard floods, your property is crying out for help. All that standing water is quietly undermining your home’s critical systems. Before we dive into solutions, let’s talk about why yards in our part of North Carolina flood so easily in the first place.

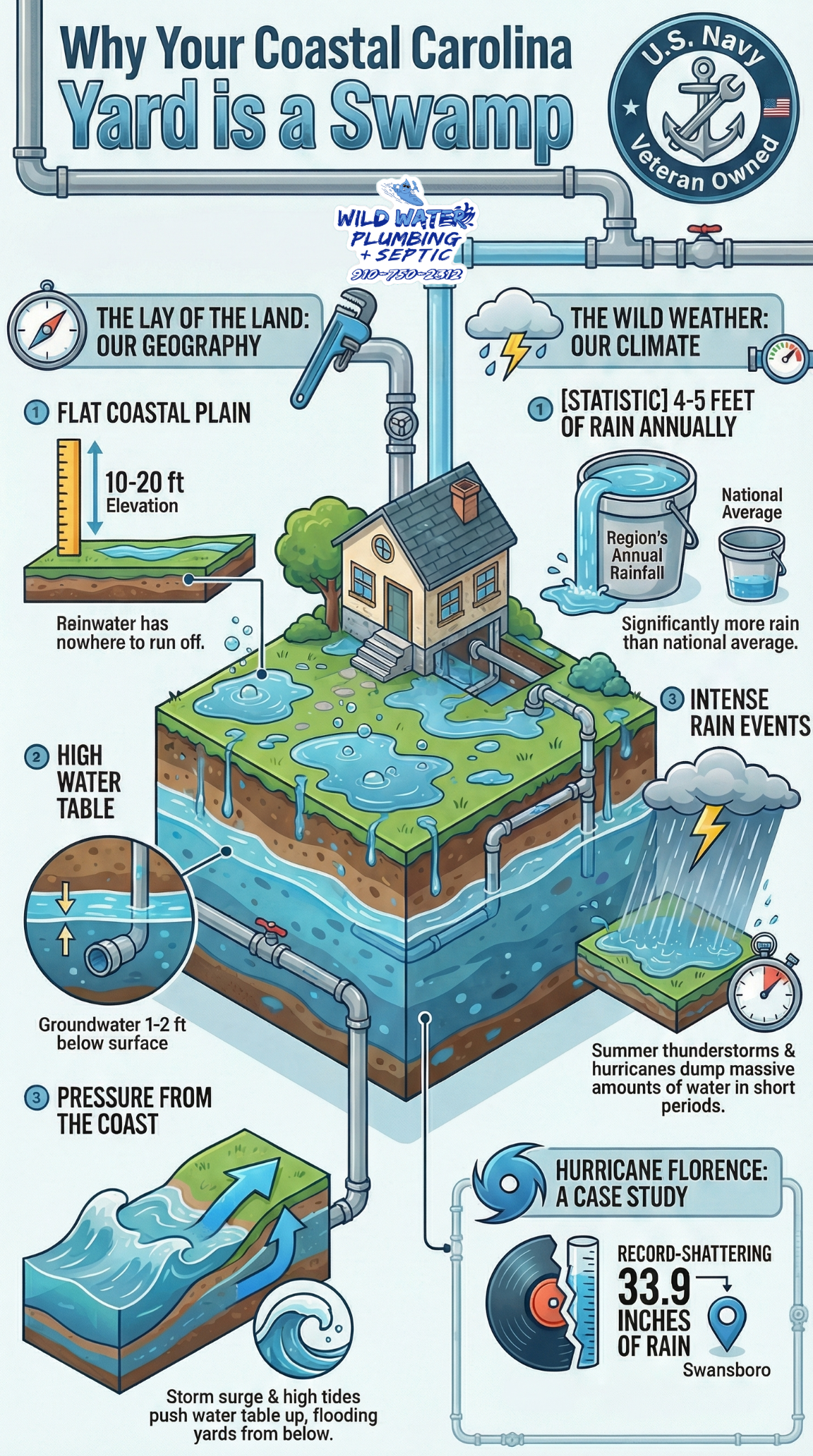

1.1 The Geography: Low, Flat, and Soaked

We’re located on the Coastal Plain, which means our terrain is very flat and barely above sea level in many areas. Great for beach days, not so great for drainage. When heavy rain falls, the water has trouble running off – there are no hills to channel it away, and much of the soil is already saturated. In fact, many properties sit at only 10–20 feet above sea level, and some barrier island communities are essentially at sea level (Source). Combine that with a high water table (the groundwater is often just a foot or two below the surface), and you have a recipe for standing water. Simply put: the ground hits “full” fast, and any extra rain becomes runoff or puddles.

To make matters worse, Eastern North Carolina’s climate is wet and wild. We get around 4–5 feet of rain per year, well above the national average (Source). Much of that comes in intense bursts – think summer thunderstorms and hurricanes. For example, Hurricane Florence in 2018 shattered state records, dumping 33.9 inches of rain in Swansboro and over 35 inches inland near Elizabethtown. When the sky can unload three feet of water in a weekend, even the best yards will struggle to drain.

And it’s not just direct rainfall – storm surge and high tides can influence drainage for coastal properties. When a big storm pushes the ocean or sound inland, or even during a regular king tide, the water table can rise into your yard from below. This is especially true in waterfront communities and barrier islands where the line between “yard” and “marsh” is blurry.

Let’s break down some local specifics by county, because each area of our region has its own twist on the drainage challenge.

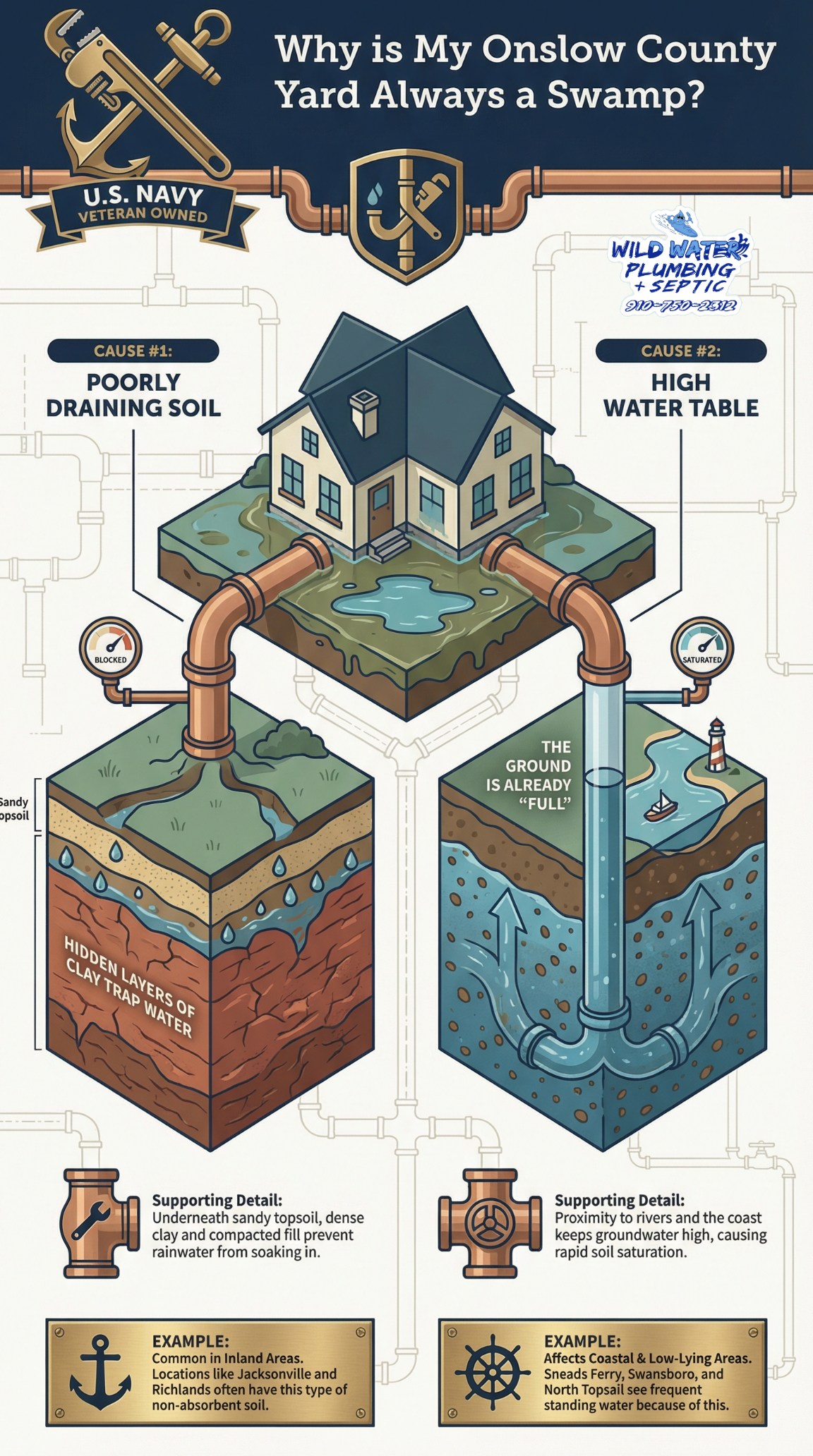

1.2 Onslow County: Clay Soils and High Water Table

Here in Onslow County – including cities and towns like Jacksonville, Holly Ridge, Swansboro, Richlands, North Topsail Beach, and Surf City – we face a double whammy of soil and water issues. Parts of Onslow have surprise pockets of clay and dense subsoil beneath the sandy top. Areas around Jacksonville and Richlands, for instance, often sit on a mix of sandy clays and compacted fill dirt from past construction. These soils don’t absorb water quickly, so heavy rain tends to pond on the surface. Other parts of the county (Sneads Ferry, North Topsail, Swansboro) are coastal and have looser sand but a very high water table. The New River and Intracoastal Waterway keep groundwater elevated. When a thunderstorm hits, or we get a few inches of rain, the soil reaches its saturation point within minutes – water has nowhere to infiltrate.

What does that look like for homeowners? Swampy yards are common. If you’re in, say, Half Moon or Pumpkin Center (suburbs outside Jacksonville), your yard might turn into a mud pit after a rain because the soil is essentially full from previous rains. In low-lying communities with names like Haws Run, Back Swamp, or Verona, the name says it all – these areas were historically wetlands or creek bottoms. I’ve visited properties in Back Swamp where even a normal rain leaves inches of standing water that linger for days. Midway Park and Piney Green, near the base at Camp Lejeune, have very flat terrain; water that falls there drains slowly toward creek outlets, often pooling along the way. Out in Dixon, Folkstone, and Petersburg on the county borders, you’ll find a lot of marshy ground and poorly drained fields. Homeowners there see their yards turn into “lakes” with surprising frequency.

Even parts of Sneads Ferry and Holly Ridge that seem elevated can have hidden low spots or ditches that overflow. I get calls from Sneads Ferry folks whose backyards stay mushy and never fully dry out between weekly summer storms. And on North Topsail Beach, which is a barrier island, it’s a constant battle: the sandy soil drains fast normally, but when the groundwater is high or during high tide, that sand can’t drain at all – the result is standing saltwater in yards after any heavy rain.

In short, Onslow County’s mix of clay patches, shallow groundwater, and flat terrain means rainwater doesn’t disappear like we’d hope. Instead, it collects in yards, around foundations, and over septic fields. Next, we’ll see that Onslow isn’t alone – our neighbors have their own water woes too.

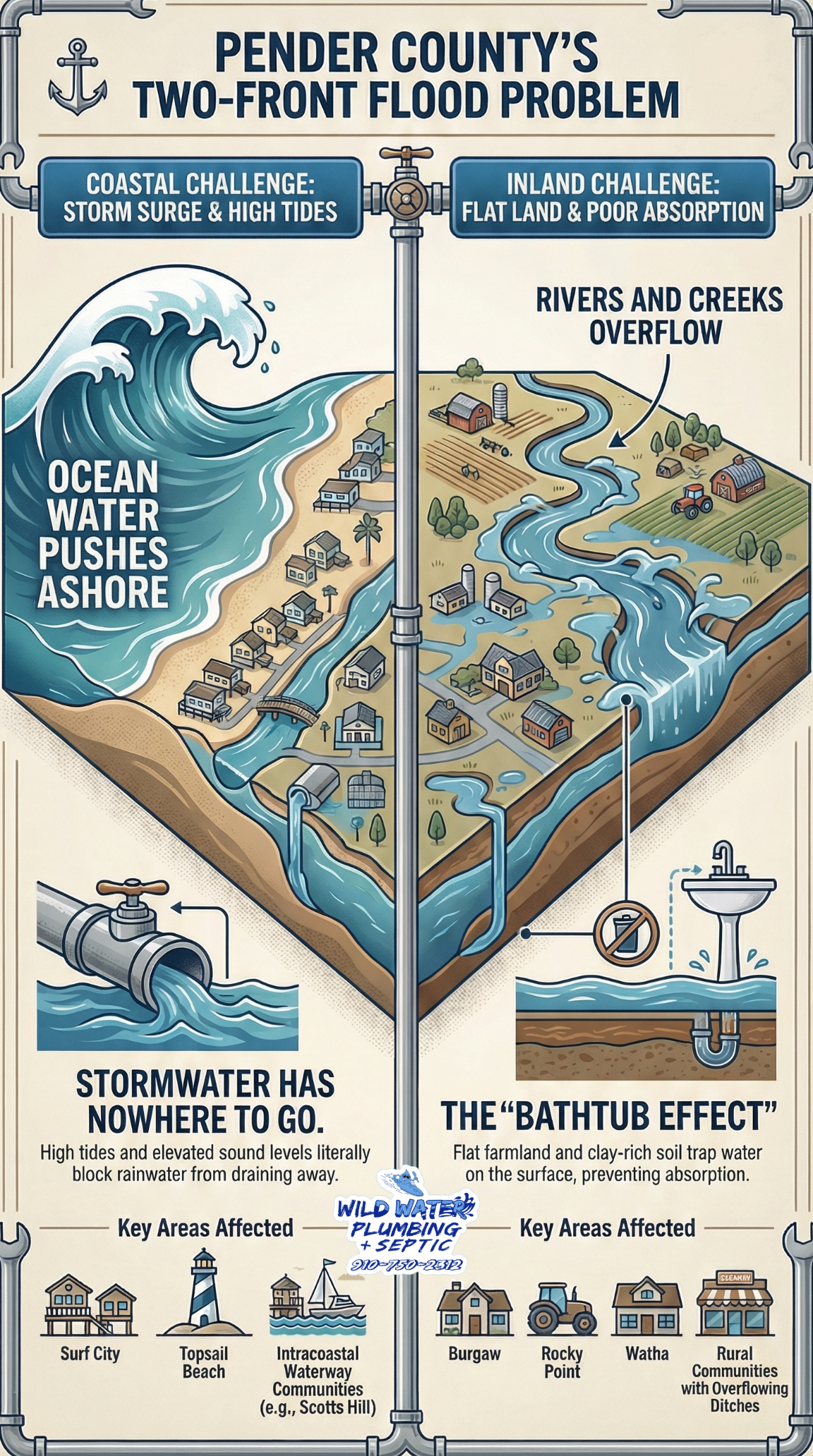

1.3 Pender County: Storms and Standing Water

Moving just south and east to Pender County (places like Burgaw, Hampstead, Surf City, Topsail Beach, Atkinson, Watha, and Rocky Point), the challenges shift a bit. Pender has a long coastline and lots of inland swampland. The coastal towns – Surf City and Topsail Beach – sit on barrier islands and low-lying mainland areas. They endure storm surges from hurricanes and nor’easters, plus regular drenching from summer squalls. When big coastal storms hit Pender, stormwater has nowhere to go except across yards and into low spots (Source). Streets flood, yards flood, and it can take many days to drain because the ocean and sounds might be literally pushing back via high tide.

Inland Pender isn’t off the hook either. Burgaw, the county seat, is infamous for flooding – it’s along creeks that feed the Northeast Cape Fear River. After hurricanes Matthew and Florence, parts of Burgaw were under feet of water for weeks. Even in routine heavy rain, yards in Burgaw’s low neighborhoods get saturated quickly. Rocky Point, Currie, Willard, and Atkinson are rural communities with flat farmland and clay-rich soil. After a downpour, those farm fields and yards act like a giant bathtub – water stands on the surface because the ground is too flat to drain and often too compacted to absorb much. I’ve seen ditches in Watha and St. Helena overflowing into yards because they can’t carry the volume of runoff fast enough.

It’s worth noting Pender also has areas like Scotts Hill and Sloop Point along the Intracoastal that are similar to Onslow’s coastal communities: very high water table and proximity to marshes. If you live in Scotts Hill or Yamacraw, for example, a heavy rain with high tide can literally cause groundwater to bubble up into your yard. And smaller localities like Charity, Montague, and Register (which many might not have heard of) often sit near creek junctions or low spots that flood after big storms.

The bottom line in Pender: whether you’re on the beaches or further inland, water tends to linger. The combination of coastal stormwater and interior flat terrain means yards flood easily and dry out slowly. Without intentional drainage solutions, a Pender County yard can stay soggy long after the clouds part.

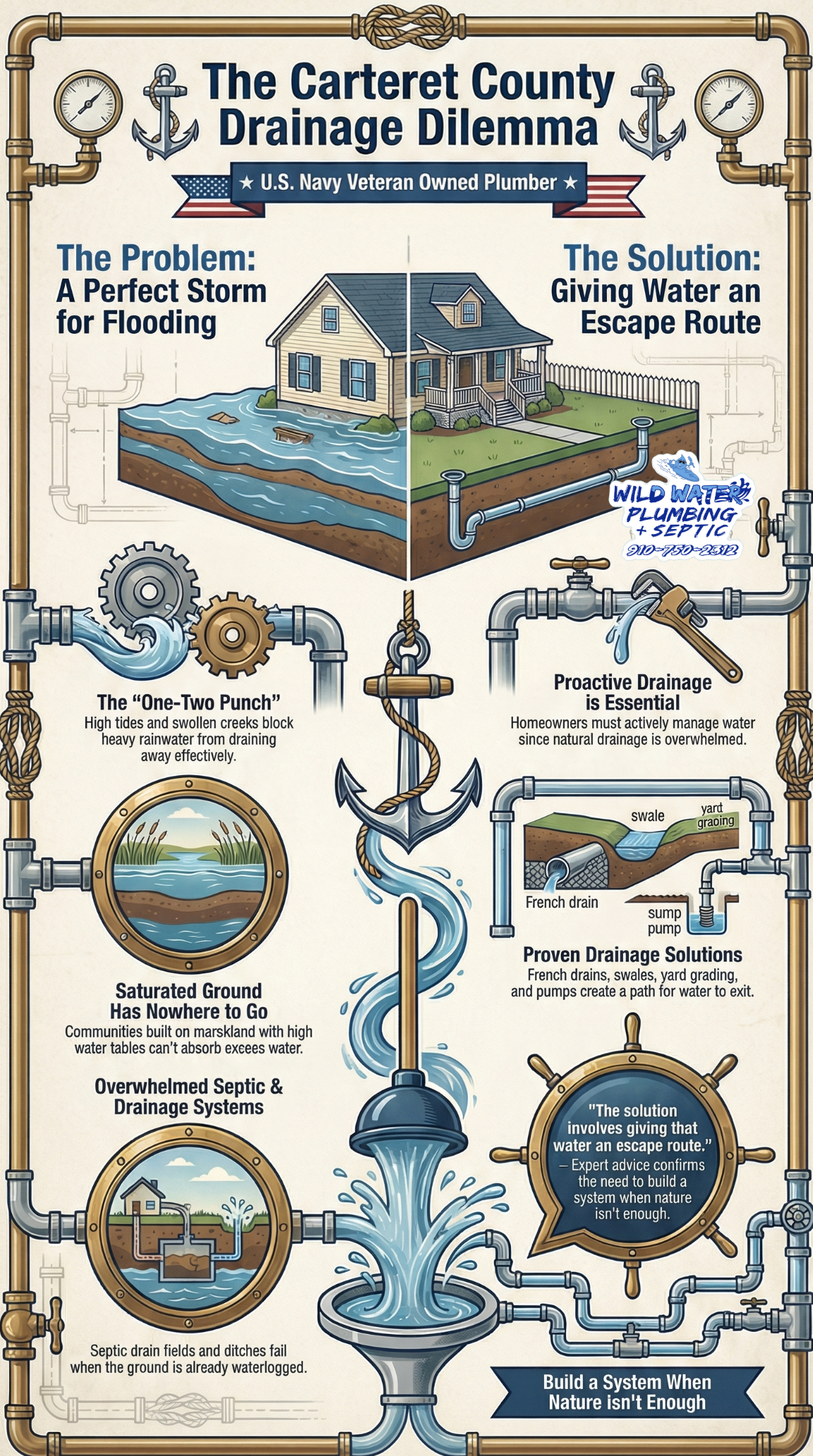

1.4 Carteret County: Tidal Flooding Inland

Heading east to Carteret County – home to places like Morehead City, Beaufort, Newport, Cape Carteret, and Cedar Point – we enter the heart of the Crystal Coast. Carteret County is surrounded by water on almost all sides (Atlantic Ocean, Bogue Sound, rivers and creeks). Many communities here are built on or near marshland, and a lot of homes use septic systems on marginal land. As a result, when you mix heavy rain with high tides, the ground often holds more water than it was ever meant to.

For example, Cedar Point (right across the bridge from Swansboro) sits along the White Oak River and the Intracoastal waterways. If you live in Cedar Point or nearby Cape Carteret, you know that a strong high tide or minor storm can push tidal water into yards and ditches. During big rain events, I’ve seen yards there with saltwater standing a foot deep, because the rainwater can’t drain out – the tide actually floods the downstream end. Morehead City and Beaufort face similar issues from Bogue Sound; parts of those towns have drainage pumps and canals, but individual yards still flood when the capacity is overwhelmed.

Inland in Carteret (toward Newport or Peletier), the elevation rises slightly, but those areas have a lot of creeks and a high water table too. When a tropical storm dumps rain, those creeks back up and flood the flat lands. Septic drain fields in places like Newport can saturate quickly from both above (rain) and below (rising groundwater). It’s a one-two punch – even if the rain stops, if the tide is high or the creek is swollen, your yard still can’t drain.

So in Carteret County, coastal flooding and poor natural drainage combine to keep yards soaked. Homeowners must be proactive with yard grading, swales, and drains to keep their property above water (literally). Trust me, I get plenty of calls from Cedar Point/Cape Carteret folks whose yard “has become a marsh” – often the solution involves giving that water an escape route via French drains or pumping, since nature isn’t doing the job on its own.

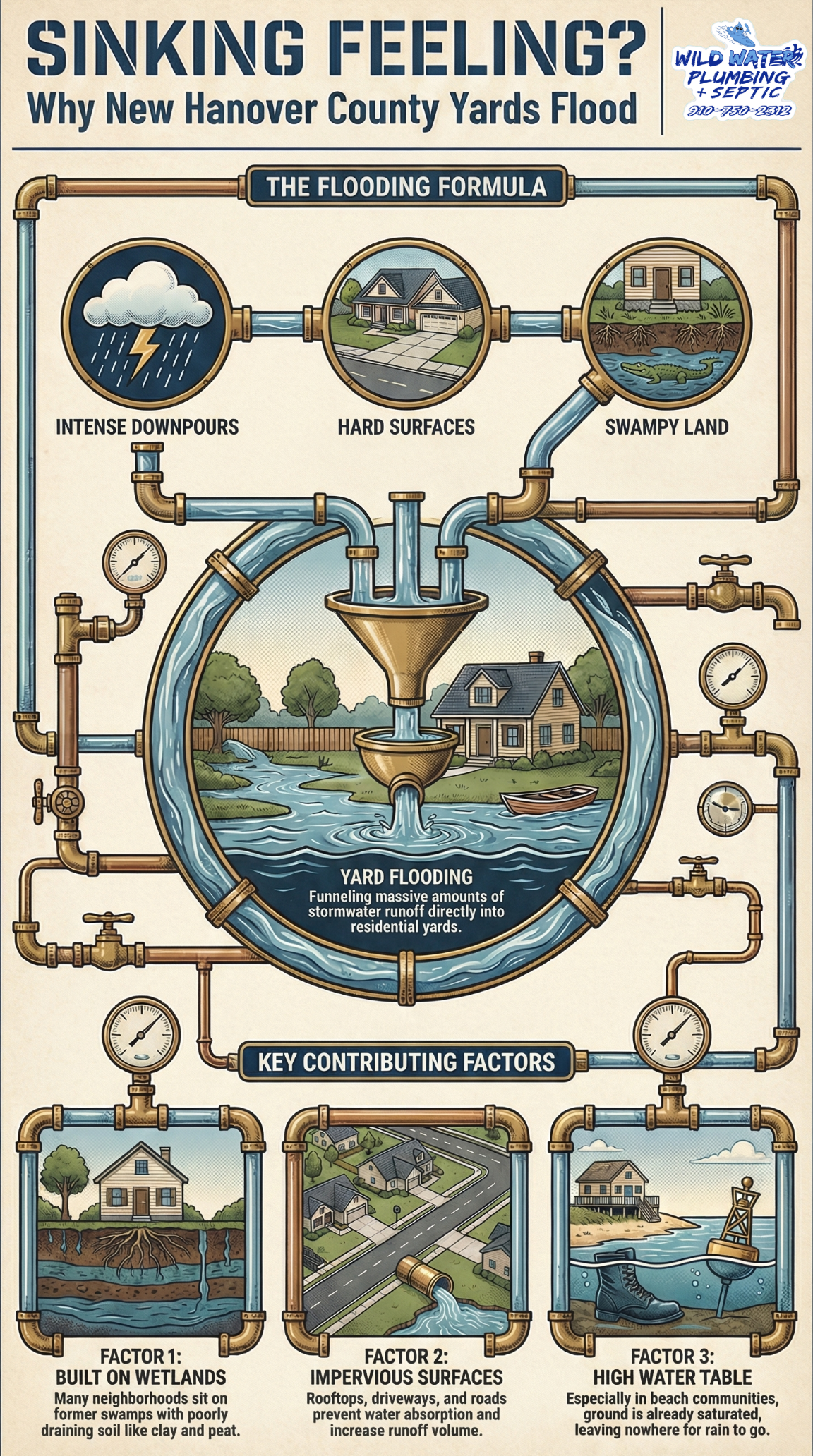

1.5 New Hanover County: Built on Wetlands

Finally, let’s talk about New Hanover County, which includes Wilmington, Carolina Beach, Kure Beach, Wrightsville Beach, and suburban areas like Castle Hayne, Ogden, Porters Neck, Bayshore, Myrtle Grove, and more. New Hanover is highly developed – more urban than the other counties – but that actually exacerbates drainage issues. Many neighborhoods around Wilmington were built on what used to be swamps, wetlands, or pine forests that naturally held water. When they put in subdivisions, they often used fill dirt to raise the ground, but underneath that fill, the soil might still be clay or waterlogged peat. Plus, all the roads, driveways, and rooftops create impervious surfaces that make runoff worse (Source). In areas around Murrayville, Kings Grant, Castle Hayne, etc., stormwater that once spread out over a swamp now funnels into yards and low spots in neighborhoods.

Wilmington itself has a decent storm sewer system, but we’ve all seen what happens in a heavy thunderstorm – intersections flood, and water can back up into yards. If your yard is at the low point of a subdivision in northern Wilmington (say in Ogden or Northchase), you might get everyone’s runoff pooling on the lawn. And the beach communities (Carolina, Kure, Wrightsville) have sandy soil but an extremely high water table, so any rain with a bit of storm surge can leave standing water. In fact, during Florence 2018, parts of Wilmington got over 27 inches of rain and it became completely isolated by floodwaters. Many homes in places like Silver Lake and Pine Valley had water around them because the drainage canals overflowed.

Areas like Wrightsboro, Skippers Corner, and Porters Neck in the north of the county are a mix of rural and new development. They often rely on ditches and retention ponds that can overflow. I’ve worked on properties in Porters Neck where water from neighboring lots was literally streaming through the backyard because the whole development’s grading was insufficient. Sea Breeze (near Carolina Beach) is an area historically known for wetlands – unsurprisingly, yards there can turn into literal lagoons in bad weather.

To sum up New Hanover: intense downpours + lots of hard surfaces + formerly swampy land = frequent yard flooding. Even though it’s more built-up, many homeowners still have septic systems on the outskirts and face the same ponding issues as folks in more rural counties.

All together, what’s the pattern? Across coastal North Carolina, from Onslow down to New Hanover, yards flood easily because of heavy rainfall, flat terrain, high water tables, and insufficient absorption. When your yard floods or stays mushy, it’s not just “how things are” – it’s a sign that your property can’t move water fast enough. And that water is starting to attack the parts of your home that matter most.

In the next section, we’ll uncover the hidden dangers lurking when water stands in your yard or under your house. It’s a lot more serious than muddy shoes – we’re talking septic system failure, foundation damage, mold growth, erosion, pest infestations, and even financial hits. Buckle up (or maybe I should say, put your waders on), because I’m going to walk you through exactly what can go wrong when proper drainage is missing.

Hidden Dangers of Poor Yard Drainage

When I visit a client with a flooded yard, they usually point to the big puddles and say something like, “It’s so annoying, my kids (or dogs) can’t even play out here!” Sure, a wet yard is inconvenient – but the real danger is what you can’t see. Standing water and chronically wet soil are quietly wreaking havoc on your property’s vital systems. Let’s break down the many ways that poor drainage can damage your home and even your health:

2.1 Septic System Destruction

If you have a septic system, it’s probably the most vulnerable thing on your property when the yard is flooding. In our region, a massive portion of homes rely on septic – nearly 48% of North Carolina properties use septic systems (over 2 million systems statewide) (Source). These systems are essentially living, breathing filters under your lawn. They depend on the soil’s ability to absorb and treat wastewater from your tank. When that soil is saturated with rainwater, a septic drain field stops working – it’s like trying to soak up a spill with an already-soaked sponge.

Here’s what happens in a waterlogged drain field:

- Wastewater can’t drain downward: The septic effluent (partially treated water from your tank) normally percolates into dry soil. But if the ground is already full of rainwater, the effluent has nowhere to go. It stops moving down and instead stays near the surface. In bad cases, it even rises up through the grass or puddles on top of your yard – yes, that means septic water mixing with those rain puddles.

- The soil’s treatment capacity vanishes: A healthy drain field needs oxygen in the soil for microbes to break down contaminants. But when soil pores flood with water, no oxygen is present. The beneficial bacteria die, and the soil can no longer “clean” the wastewater. Essentially, your septic system loses its treatment stage, so even if water is leaving the tank, it’s not being purified.

- Solids back up and clog the works: With nowhere for liquids to go, the septic tank can overfill. The pressure can force sludge and solids that should stay in the tank out into the drain lines, clogging the pipes and gravel. The field gets coated with sludge, making it even less able to absorb water. This often shortens the lifespan of the drain field drastically – a field that might have lasted 20+ years can be ruined in a much shorter time if it’s frequently flooded.

- Gurgling and slow drains in the house: One warning sign is that when your yard is saturated, your home’s toilets and sinks start acting up. You might hear gurgling sounds and notice that flushing is sluggish or that drains are slow right after a heavy rain. That’s because the septic water isn’t percolating away; it’s backing up the system all the way into your household plumbing.

- Total failure and sewage backup: If nothing is done, the result is a complete septic failure. The drain field clogs, and effluent backs up into the tank and then into your house or yard. You could end up with sewage backing up in your toilets or surfacing in your lawn – an unpleasant and dangerous situation.

I’ve seen this pattern over and over in neighborhoods across Onslow, Pender, Carteret, and New Hanover. For instance, in Jacksonville and Richlands, if a yard sits a little low, stormwater will pool right over the septic drain field, leading to these issues. In Surf City or North Topsail Beach, homes near marshes have almost no place for water to go during high tide plus heavy rain, so the septic systems there are constantly under assault. And in places like Beulaville or Wallace (Duplin/Pender area) where the soil is heavy, the ground stays wet long after a rain, so the drain field never gets the dry spell it needs.

Aside from the mechanical failure, an oversaturated septic is a health and environmental hazard. When sewage effluent can’t filter properly and adequately bubbles up, it can contaminate groundwater and nearby waterways, not to mention create awful odors and health risks in your yard. (Ever seen your lawn develop inexplicably green, lush grass over the drain field after rains? That can be a sign of septic leachate coming to the surface – essentially fertilizer in the wrong place.)

Bottom line: If you don’t give that yard water somewhere to go, it will choke your septic system to death. Repairs can run tens of thousands of dollars for a new drain field, not to mention the disruption. And as many coastal NC homeowners learned after hurricanes, flooded septic systems often aren’t covered by insurance or FEMA aid – it’s on you as the homeowner to fix it (Source). So, protecting your septic with proper drainage is absolutely critical around here.

2.2 Foundation Damage and Structural Issues

Think your house itself is safe from a soggy yard? Unfortunately, your foundation and the structural integrity of your home are very much at risk from poor yard drainage. Water is persistent – if it’s pooling next to your house, it will find a way in or cause damage over time.

Here are a few ways standing water can hurt your foundation and structure:

- Soil Erosion Under the Foundation: After rains, do you notice water ponding along your foundation walls or under your home (if you have a crawlspace)? That’s a red flag. Standing water at your home’s perimeter signals poor drainage and can erode the soil supporting your foundation (Source). Over time, as that supporting soil is washed away or softens, parts of your foundation may lose support. This can lead to settling and cracking. I’ve seen crawlspace piers sink because the footers were on soft, wet ground that eroded. Even concrete slab foundations can crack if the earth beneath them isn’t solid. Heavy rainfall and poor drainage can literally undermine your house – one day you start seeing stair-step cracks in your brick or drywall, or a corner of the house drops slightly, all due to erosion from water exposure.

- Hydrostatic Pressure on Walls: When soil around your foundation becomes saturated, it gets heavy. Waterlogged soil exerts a lot of pressure – called hydrostatic pressure – against foundation walls. If you have a basement (rare here, but some homes have partial basements or lower levels) or even a crawlspace wall, that pressure can cause cracks or bowing. Even in slab houses, saturated ground expanding and contracting can stress the concrete. Clay soils are especially problematic: they swell when wet and shrink when dry, constantly moving the foundation slightly. This can lead to cracks in the slab or masonry, and doors or windows that suddenly stick due to shifting.

- Water Infiltration and Concrete Damage: Consistent standing water around the foundation seeps into tiny cracks and pores. Over time this can lead to damp or wet crawlspaces, and in winter (on the rare occasions it freezes) that water can freeze and expand, widening cracks. Even without freezing, chronic dampness degrades concrete and mortar. You might notice efflorescence (white mineral deposits) on block walls, indicating water penetration. If you have a crawlspace, the piers and wood framing can suffer – water entering brings moisture that can rot wood or rust metal supports.

- Mold and Mildew in Crawlspace/Basement: This crosses into the next section, but it’s worth mentioning here: water around the foundation often means water under the house. Many homes here have vented crawlspaces. When the soil under your home is wet or there’s standing water, it dramatically raises humidity in the crawlspace. The result is often mold growth on joists and subfloor, musty odors, and even structural wood rot if left unchecked. I’ve crawled under homes in coastal NC and found mushrooms growing on the wood – not a good sign! Studies have shown that damp crawlspaces lead to elevated mold spore counts inside the home (Source), which can affect your family’s health (more on that soon).

- Foundation Cracks and Movement: Over months and years, poor drainage can cause your foundation to move unevenly. Signs of this include cracks in your exterior bricks, cracks in interior drywall (often above doors or windows), or uneven floors. Doors and windows might go “out of square” (sticking or not latching properly). These are classic symptoms of foundation settlement or movement, possibly exacerbated by soil washout or water-induced expansion. Remember, the soil is part of your foundation support system – if it’s compromised by water, your concrete and wood structure will show it.

One common scenario: Houses in low-lying parts of Wilmington or Jacksonville often have a continuous footer foundation with a crawlspace. If the yard grading is poor, water pools by the foundation wall. Over the years, that section of the foundation might start settling, leading to diagonal cracks in the brick veneer. The homeowner might not connect it to yard flooding, but indeed, erosion and saturation were the culprits.

Another scenario: In North Topsail Beach or Carolina Beach, many homes are on pilings or raised foundations. Standing water under those homes can erode the footings or rust out metal connectors. I’ve seen wood pilings with accelerated rot at the ground line because they sat in water too often. Again, drainage would have helped.

The takeaway: Water around your foundation is a big no-no. It causes erosion, pressure, and moisture issues that can severely damage the structure. Fixing a foundation or structural problem can be incredibly expensive (often far more than installing a drainage solution). We’re talking $1,000–$5,000 for minor water damage repairs vs. tens of thousands if severe flooding or foundation repairs are needed (Source). It pays to keep water away from your house in the first place.

2.3 Soil Erosion and Landscape Damage

Even if we ignore the septic and the house (which we shouldn’t!), a poorly drained yard will wreck itself over time. Erosion is a major issue in yards with unmanaged runoff. You might not live on a hill – most of us don’t here – but water will still find paths to wash away soil, kill grass, and create hazards.

What I often see in yards with drainage issues:

- Gullies or Washed-Out Areas: If water is flowing across your property (for instance, draining off the driveway or coming from a neighbor’s lot), it can cut small channels in your yard. Over time these become ugly gullies or ditches where the topsoil is completely eroded. It’s not just a cosmetic issue; it can expose foundations of fences, undercut patios, or create uneven ground that’s hard to mow or walk on. In one case in Sneads Ferry, a homeowner had runoff from the road slicing through his side yard – it eventually washed out so badly that a shed began to lean.

- Bare, Muddy Patches: Standing water will smother your grass. Lawns need oxygen in the soil; when soil is waterlogged, roots can’t breathe and grass dies off. You’re left with persistent bare patches of mud where nothing grows. These tend to coincide with low spots that collect water. Not only is it unsightly, but bare soil then erodes even faster because there’s no grass to hold it together. It becomes a vicious cycle of mud and erosion. I often tell clients: those “problem spots” in the lawn that never stay green are trying to tell you something – likely that they’re too wet too often.

- Settling and Sinkholes: In extreme cases, poor drainage can contribute to sinkholes or settling of the ground. For example, if there was any buried debris or loose fill (not uncommon in new developments) under your yard, flowing water can create voids as it carries fines (small soil particles) away. I’ve seen shallow sinkholes appear in yards where a corrugated drain pipe failed and leaked underground for months – suddenly, the homeowner has a 3-foot pit in the yard. Chronic saturation can also cause the ground to settle unevenly, affecting sidewalks, driveways, or garden structures. In older parts of Jacksonville, I’ve encountered front walkways that sank because the soil below was constantly soft from gutter downspouts not being routed away.

- Damage to Landscaping and Trees: Many of us invest in gardens, flowerbeds, and trees to beautify our homes. Those can suffer if your yard doesn’t drain. Ornamental plants generally don’t like “wet feet” – their roots will rot in swampy soil. You might notice shrubs turning yellow or stunted in the wet zones. Likewise, standing water can destabilize trees by weakening their root structure; in a storm, a tree in soft, eroded soil is more likely to topple. I’ve seen beautiful live oaks and pines uprooted, partly because the soil around them was loose and saturated. Additionally,the mulch and topsoil you’ve added can just wash away, wasting your money and effort.

- Mosquito Breeding Grounds: This crosses into “pest issues,” but is part of landscape damage too. Those puddles and swampy areas in the yard? Mosquitoes love them – stagnant water is prime breeding habitat. Within days of water standing, you can get a bloom of mosquito larvae. Not only is this a nuisance (say goodbye to enjoying your yard in the evening), but it’s also a health concern since mosquitoes can carry diseases. Your yard essentially becomes part of the mosquito breeding wetlands if it’s always wet. (I’ll elaborate more on pests in a moment, but it’s worth noting here that erosion can create little potholes and depressions that hold water, which then invite mosquitoes.)

In summary, poor drainage scars your landscape. You end up with a yard that looks uncared for – ruts, bare mud, patchy grass, maybe even minor sinkholes. And the fixes aren’t simple cosmetic ones; you have to solve the water issue first. Otherwise, you’ll lay new sod or soil and watch it wash away again. A well-drained yard, conversely, stays solid, green, and safe. You can maintain it more easily and enjoy it more. If you ever plan to sell your home, a yard full of erosion scars and muddy areas is a big turn-off (and a red flag to inspectors). Which brings us to some human factors: health and value.

2.4 Mold, Mildew, and Indoor Air Quality

We touched on this under foundations, but let’s dive deeper: excess moisture from poor drainage can lead to serious mold and mildew problems, which affect not just your house, but your health.

In Eastern NC’s humid climate, keeping a crawlspace or basement dry is already a challenge. Add yard flooding to the mix, and you’ve got the perfect conditions for mold. Here’s how it happens:

- Damp Crawlspaces: Most homes here have a crawlspace with foundation vents. The idea (in older building practice) was that vents allow moisture to escape. In reality, especially in NC, those vents often let more moisture in – the air outside is so humid that vented crawlspaces end up very damp (Source). Now, if your yard is often wet, that means the ground under your house is also wet. I’ve seen standing water inches deep in crawlspaces after heavy rains because water seeped under the footings. Even when it’s not that dramatic, chronically wet soil under the house means the humidity in the crawl stays high. Wooden joists, subfloor, and beams soak up that moisture. Within days, you can get mildew odors. Within weeks, you might see mold growth on wood surfaces (gray, white, or green fuzzy stuff). Given time, this can rot the wood, weakening your floor structure. It also tends to attract pests like wood-boring insects (they love moist wood).

- Mold in Living Areas: You might think the crawlspace is separate from your living room or bedrooms, but about 40-50% of the air in your first floor can come from the crawlspace (the “stack effect” draws air upward). So if your crawlspace is moldy and mildewy, guess what – your indoor air is being contaminated. Studies in the Southeast have linked high crawlspace moisture to high mold spore counts inside the home (Source). Many clients report aggravated allergies, musty smells in the house, or even visible mold in closets or on baseboards. Mold isn’t just gross; it can cause respiratory issues, trigger asthma, and generally decrease indoor air quality. Black mold (Stachybotrys) can grow on constantly wet materials and is a known toxin. So a wet yard can indirectly lead to a mold-infested home, which is a serious health concern.

- Mildew and Mold in Basements/Garages: A few homes might have partial basements or enclosed lower levels (or even just a slab-on-grade garage). If water is not draining, these areas can experience seepage. You might walk into your garage and notice the concrete floor is sweating or has dark mildew spots around the edges – that can be from water intrusion. Finished lower-level rooms can develop mold behind drywall if there’s a leak from outside. I’ve seen folks dehumidifying their basements constantly, when the root issue was that their yard grading was sloped toward the house causing water intrusion.

- Odors and HVAC Impact: Mold and mildew create that characteristic “musty” smell. If it’s in your crawlspace or basement, that odor can eventually spread throughout your whole house. Additionally, if your HVAC ductwork runs in the crawlspace (common in this region), and the crawl is wet, those ducts can accumulate condensation and organic dust – a recipe for mold inside the ducts. Then every time the AC kicks on, it may blow mold spores throughout the house. So poor drainage can lead to a chain reaction: wet crawl -> moldy ducts -> whole-house air contamination.

- High Utility Bills: Not directly “damage,” but as an aside – a wet crawlspace also drives up energy costs. Wet air takes more energy to cool, and your HVAC will work harder. We often end up installing vapor barriers and drains to dry a crawlspace, and clients notice an immediate improvement in comfort and sometimes lower energy bills. A damp house is harder to heat and cool.

The key point: Water where it shouldn’t be leads to mold and health hazards. Proper drainage protects your home by keeping the underbelly dry. If you’ve already got musty smells or suspect mold due to past flooding, you may need a professional remediation and crawlspace sealing. But the first step is always stop the water at the source – don’t let your yard turn into a moisture supplier for your home’s interior.

2.5 Pest & Wildlife Problems (Mosquitoes, etc.)

Water attracts life – unfortunately, not the kind of life you want in your yard or home. If your property has standing water or is consistently damp, you may unwittingly be inviting a host of pests and other wildlife issues.

Mosquitoes: Let’s start with the obvious. Coastal NC is mosquito country in the warm months anyway, but a flooded yard makes it 100x worse. Mosquitoes need stagnant water to breed – even a few days of standing water is enough for eggs to hatch. Those puddles in the low corners of your lawn, or water pooled in a ditch, become mosquito nurseries. Next thing you know, you can’t step outside at dusk without becoming a snack. This is not only a quality-of-life issue; it’s a health risk. Mosquitoes can carry West Nile virus, Eastern Equine Encephalitis, and other diseases. We’ve had cases of mosquito-borne illnesses in NC. By not draining your yard, you’re essentially farming mosquitoes. Clients sometimes tell me “I can’t enjoy my porch at all in summer because the bugs are so bad,” and I point out the swampy yard as a major culprit. Eliminating standing water goes hand-in-hand with any mosquito control plan.

Other Insects: Aside from mosquitoes, standing water and wet soil attract other pests. Termites, for instance, are drawn to moist wood – a chronically damp foundation or waterlogged mulch bed can attract termite colonies more readily. Fire ants (a big issue in the South) often move to higher ground (like into yards) during floods, and they can establish mounds in soft, wet soil. Wet conditions also attract roaches and water bugs looking for a damp habitat. Fungus gnats and other small flying insects also thrive in soggy soil conditions. If you notice an uptick in creepy-crawlies around your home, excess moisture could be a root cause.

Rodents: Believe it or not, rats and mice also appreciate it when humans inadvertently provide them with water sources. A yard that holds water might attract rodents who come to drink or feed on the increased insect population. Also, if your crawlspace is wet and open, rodents may find it a hospitable environment (nice and cool in summer). I’ve found evidence of mice nesting in insulation of very damp crawlspaces – likely because the humidity made it more comfortable for them, and fewer people go into a nasty, wet crawlspace to disturb them. While drainage alone won’t guarantee no rodents, it removes one attractant (water) and helps keep areas less hospitable to them.

Snakes and Wildlife: Here in Eastern NC, snakes are on people’s minds. Non-poisonous water snakes and even venomous cottonmouths love wetlands and standing water. If you live near a creek or swampy area (or your yard has turned into one), you might encounter snakes more often. They follow frogs and other small critters attracted to the water. I’ve had a few customers in Back Swamp and Holly Ridge report more snake sightings in their yards during wet seasons. While most snakes are harmless and even beneficial, it’s understandable not to want them right by your house or where kids play. Reducing ground moisture can make your immediate property less appealing to them (they’ll stay nearer the real swamp).

Additionally, waterfowl and other wildlife might treat your yard like a pond. I’ve seen yards so flooded that ducks come in for a landing! Again, not necessarily “damage,” but you probably don’t want your lawn to double as a wetland habitat. Larger wildlife, such as deer or raccoons, may trample a wet yard more (soft ground shows tracks and damage more readily).

Secondary damage from pests: Remember that pests attracted by water can cause their own damage – termites eating wood, rodents gnawing wires, etc. Mold (a fungus) can even be considered a pest in this context. It all ties together: a dry yard and crawlspace tends not to attract as many pests as a soggy, musty one.

So, managing drainage isn’t just about water itself – it’s about breaking the chain of conditions that invite infestations. A French drain or better grading can literally mean fewer mosquito bites and a lower chance of finding a snake under your steps. That’s a pretty compelling argument for many homeowners, beyond the structural stuff.

2.6 Property Value Loss and Selling Problems

All the issues above, septic failures, foundation cracks, mold, erosion, pest problems, don’t just cost you money to fix; they can also devalue your property and make it harder to sell your home if you ever choose to. Even if you’re not planning to sell soon, it’s wise to protect your biggest investment (your home) from anything that could diminish its worth.

Here are some real considerations:

- Disclosure and Buyer Turn-Off: In North Carolina, sellers must disclose certain problems to potential buyers. While there isn’t a specific question like “Does your yard drain poorly?”, you are obligated to disclose things like water intrusion, drainage issues, or septic malfunctions if they’re ongoing problems. And believe me, savvy buyers or home inspectors will spot signs of poor drainage: lingering puddles, foundation water marks, sump pumps running overtime, efflorescence or mold in crawl, etc. These are red flags. A buyer might walk away or demand repairs/upgrades before closing. There’s even a push to include more flood history on disclosure forms because a home that has flooded once is likely to flood again (Source). If your property has a reputation for being “the one with the swampy yard,” you can expect trouble selling it.

- Lower Appraisal and Value: Ongoing water problems can directly reduce a home’s appraised value. One study noted that if a house is in a designated floodplain (higher flood risk), it can knock around $11,000 off the asking price on average (Source). If the property has a history of water damage or drainage issues, the value could drop even more – one figure estimates around 7.3% reduction of overall value for a home with constant water problems (Source). On a $300,000 home, 7% is over $20k lost. Buyers aren’t willing to pay top dollar for a property that comes with headaches. Even cosmetic issues like a yard that won’t grow grass or a persistent musty odor can affect how much someone offers.

- Repair Costs – Who Pays? Imagine you’re selling your house, and during the inspection, the inspector finds mold in the crawlspace and a failing septic system, both due to chronic water issues. A buyer could ask you to remediate the mold and fix the septic (which could be thousands and thousands of dollars) or they’ll walk, or demand a big price cut. Statistics show water issues/damage on average cost a homeowner $1,000–$4,500 to mitigate (if minor), but can easily soar to $5,000–$10,000+ for extensive foundation repairs or septic replacements (Source). Most buyers will either expect you to fix it or subtract the estimated repair from the price. Either way, you’re paying – whether upfront to install drainage or later as a concession. Being proactive (fixing drainage now) could actually save you money when selling, because you won’t face last-minute expensive demands.

- Flood Insurance and Financing: If your yard flooding is part of a larger flood risk (like you’re in a flood-prone area), buyers might be required to get flood insurance, which can be pricey. High insurance premiums can make a home less attractive or affordable to buyers. Also, if issues are severe (such as structural cracks caused by settling), some lenders may be hesitant to approve a mortgage until they’re resolved. These are indirect effects, but real.

- Curb Appeal: Let’s be frank – a soggy, eroded yard just doesn’t look good. First impressions matter in real estate. If a potential buyer pulls up and sees a yard with patches of dead grass, muddy tire ruts, or sandbags by the garage (yes, I’ve seen homeowners resort to sandbags to keep water out of the house), it’s a huge turn-off. It gives the sense that the property is high-maintenance or has hidden problems. Even if the house is beautifully renovated inside, a poor exterior due to drainage can sour the deal. Conversely, a well-drained, lush lawn and dry foundation area instill confidence that the home is well cared for.

- Long-Term Home Value Trajectory: Beyond immediate sale concerns, consider that addressing drainage protects your home’s long-term value. Preventing damage is far cheaper than repairing it, and a home that doesn’t develop water problems will hold its value better. For instance, a home that never has a septic failure or foundation issue because drainage was handled will be worth more over decades than an identical home that had those issues and patched them. Being proactive can add 10% or more to your home’s value in the long run, just by avoiding the reputation and costs of water damage (Source).

In summary, poor drainage can literally cost you when it’s time to sell. It’s one of those unseen factors that can make or break a real estate deal. Many homeowners in our area have learned the hard way that fixing the grading or adding that French drain after you’ve already gotten water damage is too late to avoid the hit to your wallet. My advice: treat proper drainage as an investment in your home’s equity. It keeps your property more marketable and valuable.

We’ve covered a lot of doom and gloom – septic failure, foundation woes, mold, bugs, money loss – all stemming from water not being managed. The good news is, there are solutions! Chief among them for many yard situations is the French drain, a simple yet powerful tool to redirect water. In the next section, we’ll turn the corner to something positive: how a French drain (when done right) can protect your septic system, foundation, landscape, and wallet from all these dangers.

How French Drains Solve the Problem

By now, you might be thinking, “Alright, Justin, I get it – water is the enemy. So what’s the solution?” This is where I get excited because there is a straightforward solution for many drainage problems: the French drain. I often tell homeowners that a French drain is one of the most effective and affordable ways to keep unwanted water out of your yard.

Let’s break down what a French drain is, how it works, and why it’s so useful for the issues we discussed. I’ll also touch on design considerations (especially given our local conditions) and why professional installation matters.

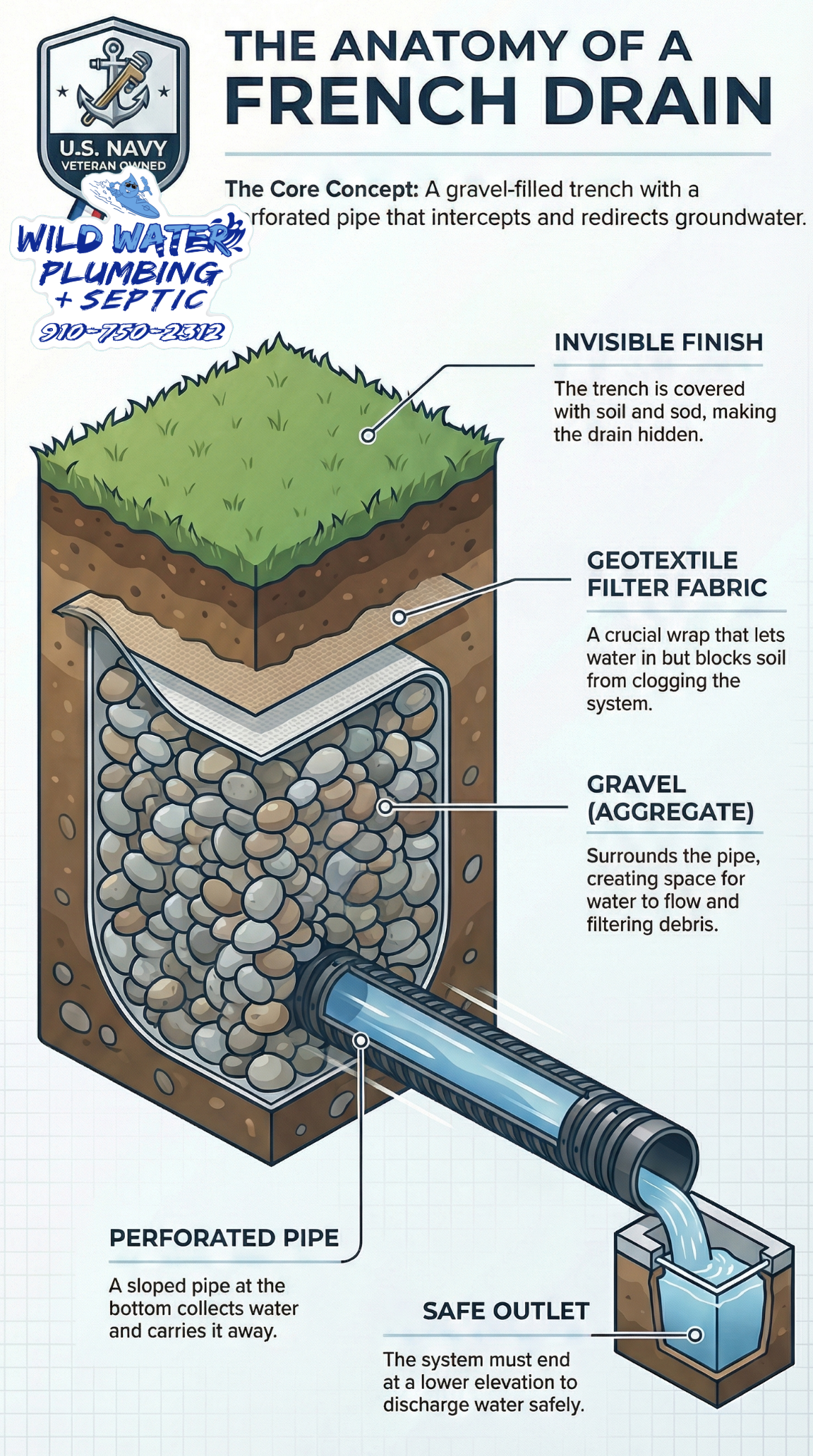

3.1 What is a French Drain? (Explained)

Despite the fancy name, a French drain is a simple concept (no, it’s not something invented in France to drain wine barrels or anything – it’s actually named after Henry Flagg French, an American, but I digress). In plain language, a French drain is:

- A gravel-filled trench in the ground, with

- A perforated pipe at the bottom of that trench,

- Wrapped in a filter fabric to keep dirt out,

- And then covered back over with soil or sod, making it invisible on the surface.

Think of it as a hidden channel that collects water and carries it away (Source). Instead of water spreading uncontrolled beneath your grass, the French drain draws water through the gravel into the pipe and then discharges it to a safe location (like a ditch, swale, dry well, or storm drain).

When rain falls on your yard, water naturally follows gravity, seeping downward and sideways. A French drain intercepts that flow. It’s typically installed in trouble spots – for example, along a low section of lawn, around the perimeter of a house foundation, or upslope of a septic field – wherever we want to intercept and redirect water.

Key components of a French drain:

- Perforated Pipe: Usually a 4-inch diameter PVC or HDPE pipe with holes (perforations) in it. The pipe is laid at a slight slope (we aim for at least 1% grade or more) so that water will flow once it’s in the pipe. The holes face downward or around the sides, allowing water to enter.

- Gravel (Aggregate): We surround the pipe in washed gravel (often 3/4” stone). The gravel does a few things: it creates lots of air space for water to flow through, it filters out larger debris, and it spreads the water to the pipe. It essentially acts as an underground reservoir and conduit for water.

- Geotextile Filter Fabric: This is a crucial but sometimes omitted detail. We wrap the gravel and pipe in a permeable fabric “sock.” The fabric lets water pass but prevents soil/silt from intruding and clogging the gravel/pipe over time. (Without fabric, many DIY French drains clog up after a year or two when fine soil fills the gaps in the gravel).

- Outlet (Discharge): The French drain must end lower than where it begins to provide a water outlet. This could be the street gutter, a culvert, a drainage ditch at the edge of the property, a dry well, or even daylighting on a lower slope. The key is that the end of the pipe must be lower than the beginning (gravity does the work – no pumps here, ideally).

- Camouflage: Typically, we’ll fold the sod or topsoil back over the trench so you don’t see an open rock strip (in some cases, people leave a gravel strip visible; that’s an option for high-flow areas). But usually, a well-built French drain is practically invisible on your lawn once it’s done.

So, picture your problem area – say, the side of your house where water stands. Now imagine a trench cut across that area with a pipe in it that secretly sucks in the water and sends it off. That’s the French drain magic.

To put it succinctly, a French drain is a hidden pathway that provides water with an easier route to drain from your yard. Water, like most of us, takes the path of least resistance. The French drain becomes that easy path, rather than your foundation or septic field.

3.2 Protecting Your Septic System and Home

Now, how does this relate specifically to all those problems we talked about? Let’s connect the dots. A properly designed French drain in our Onslow/Pender/Carteret/New Hanover context can:

- Stop Yard Flooding in its Tracks: By catching water at the worst “trouble spots” and redirecting it, French drains eliminate standing puddles in your yard. For example, if you have a corner of the yard that always becomes a pond, we might install a French drain that encircles that area and ties into a drainage ditch – so water that would stagnate there is quickly whisked away. No more swampy, unusable lawn.

- Keep Water Away from Foundations and Crawlspaces: One of the most common installations I do is a perimeter French drain around a house or along the high side of a foundation. This effectively lowers the water table near the house and prevents the hydrostatic pressure on the walls. Instead of water seeping into your crawlspace, it goes into the drain. This protects against foundation leaks and reduces crawlspace humidity. It’s like giving your home a moat, but one that takes water away. You can actually feel the difference – a crawlspace that used to be damp stays much drier after a drainage system is installed.

- Shield the Septic Tank and Drain Field: We often place French drains strategically around septic system components. For instance, putting a French drain uphill of a drain field can intercept runoff or groundwater that would otherwise flow into the field. By doing so, you prevent the field from becoming oversaturated. In essence, the drain says to the excess water, “Hey, go this way, leave this septic field alone.” Similarly, if you have a high water table, a French drain can act as a curtain drain, lowering the water table around the field. In one case in Hampstead, we installed a drain just above a client’s septic lines on a gentle slope – after that, even in heavy rains, the field stayed drier, and their septic alarms stopped going off. Protecting the septic means you extend its life and function.

- Reduce Soil Compaction and Let Your Lawn Breathe: Constantly wet soil often becomes compacted (or is compacted already). By draining water out, the soil can relax and maintain air pockets. Grass roots get oxygen again, and your lawn can recover. I’ve seen areas that were perpetually muddy firm up and start to grow grass within a season after drainage improvements. It’s rewarding to see a homeowner able to mow an area that was previously too soft to even walk on.

- Extend the Usable Life of Structures: Whether it’s your home’s foundation, your deck footings, or that shed on a slab, keeping water away extends their life. Concrete and wood remain dry and stable, meaning you won’t have to deal with rot or settlement repairs. I consider a French drain a form of preventive maintenance investment – a few thousand bucks now could save you tens of thousands in avoided structural maintenance later. I often say: Water is the #1 long-term destroyer of homes. Cut water off at the pass, and you’ve solved a massive chunk of potential deterioration.

- Improve Yard Usability: This is quality of life – after we dry up a yard, suddenly the kids can play outside after rain, you can garden without wearing waders, you don’t lose tools in mud. One client in Swansboro joked that he got “his backyard back” after we installed a French drain to dry out a corner that always flooded. No more fencing it off from the dog or constantly dealing with mud being tracked inside.

In essence, a French drain is the unsung hero protecting your property: septic safety, foundation security, healthier lawn, fewer pests, and preserved home value. It addresses the root cause (water) of so many problems at once.

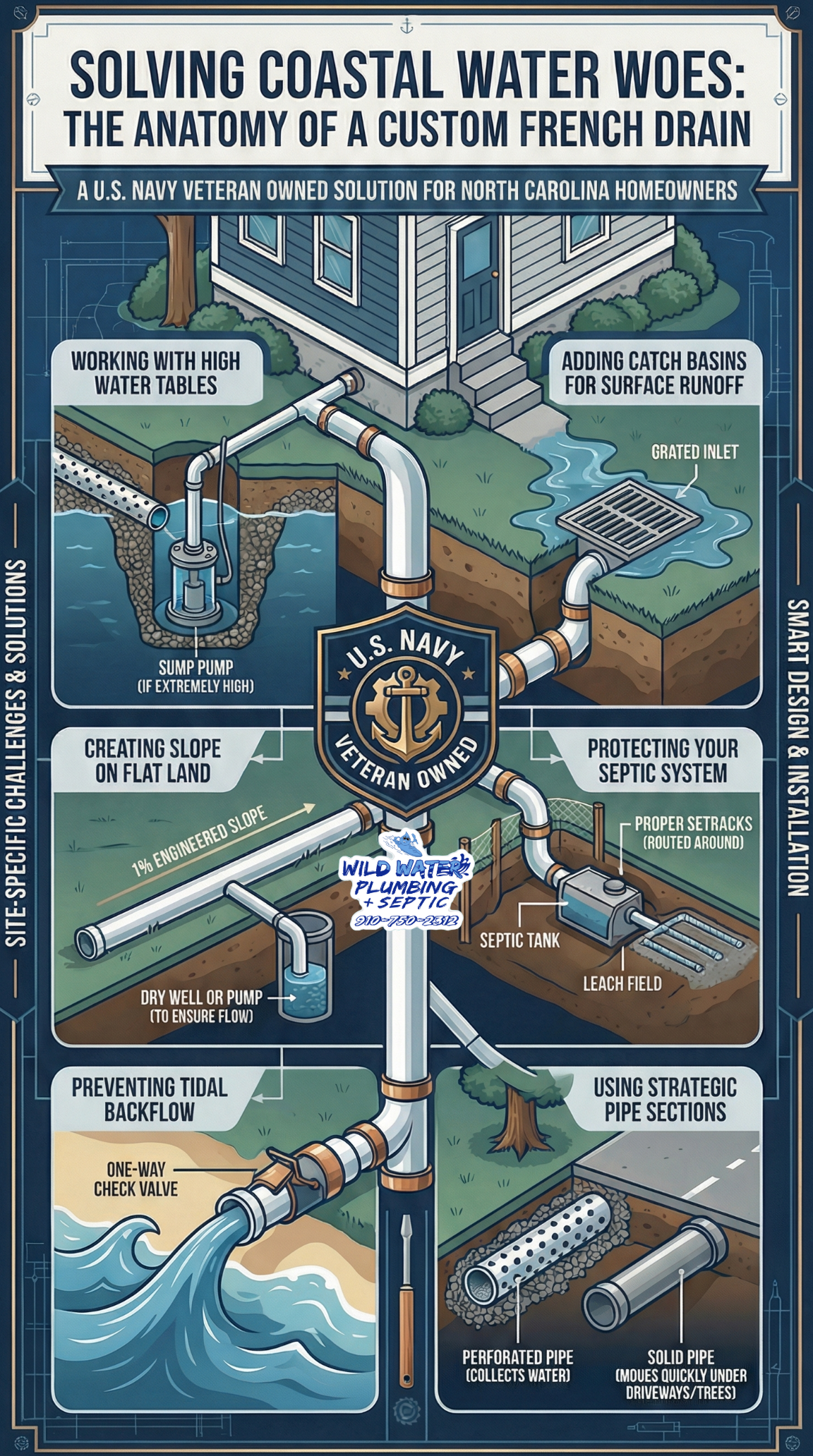

3.3 Design Matters: Tailoring to Local Conditions

Now, before you run to rent a trencher and throw pipe in the ground, a word of caution: Not all French drains are created equal. Design and placement are key, especially given our diverse conditions (remember all those specific area challenges? We factor those in!). Here’s how we tailor French drain solutions around here:

- Location, Location, Location: We identify where the water is coming from and where we can send it. For example:

- In a low area of Swansboro, I might route a French drain from the soggy back corner of the yard out to a nearby ditch or creek.

- In Hampstead or Rocky Point, if the goal is to protect a drain field, I’ll install the drain on the uphill side to catch water before it reaches the field.

- For properties near tidal waters (say Beaufort or Newport), sometimes we place French drains between the house and the marshy edge of the property to intercept both rain runoff and any creeping tidal water.

- In a suburban lot in Wilmington or Ogden, a common design is a French drain along the back fence line to catch water flowing from adjacent yards (since many newer subdivisions are graded to drain toward rear lots). This prevents “neighbor’s water” from drowning your yard.

- Depth and Water Table: Coastal NC has high water tables. We often dig French drains as deep as practical (2-3 feet down typically) to intersect the water where it’s moving through the soil. However, if the water table is extremely high (say 1 foot below grade in wet season), a French drain by itself might need augmentation (like adding a sump pump to lift water out). We consider whether we’re dealing with surface runoff vs. ground water seepage. In clay areas, water moves more on the surface, so shallower drains to catch surface flow might suffice. In sandy or loamy areas, water percolates down, so a deeper drain can slurp it up underground.

- Grading and Slope: A French drain must be sloped properly. Around here, our land is flat, so achieving slope can be tricky. We sometimes start shallow and gradually get deeper toward the outlet. We only need a drop of say 1 foot over 100 feet (1% slope) for water to flow, but we do need that drop. If the yard is pancake-flat, we may tie the French drain into a dry well or a sump that pumps the water out. Each situation we examine: what’s the closest lower point? Maybe it’s a drainage ditch at the road (common in rural areas) or a storm drain at the corner of the lot (common in city). In designing, I always visualize the path of water from where it enters our pipe to where it exits. It must be continuous and downhill.

- Avoiding the Septic Field: Crucial in design – we never install a French drain through a septic drain field. Why? Because if it’s too close, it could actually intercept your septic effluent, essentially draining your septic into the French drain (gross and illegal!). Also driving heavy equipment over a drain field can crush pipes. So, a knowledgeable installer will route around the field with proper setbacks (usually at least several feet away, if not more). We sometimes encircle a drain field at a safe distance. The goal is to protect, not disturb the septic.

- Considering Tidal or Backflow: If you’re near tidal waters, we might incorporate a one-way valve (like a check valve) on the outlet. This prevents a high tide from sending water back up the French drain into your yard (yes, that can happen if not addressed!). For instance, a French drain outlet into a canal in Surf City would need a backflow preventer so that during a storm surge the saltwater doesn’t reverse into your yard.

- Supplementary Catch Basins: In areas that get a lot of surface water (like a low spot where water pools visibly), I might add catch basin inlets to the French drain. These are like little grate-covered boxes tied into the pipe, that directly collect runoff. For example, a clay-heavy yard in Brunswick Forest (Brunswick Co. just south of us) might utilize catch basins since water isn’t soaking into the ground anyway. In Onslow or Pender, I do this if I see a lot of sheet flow or if gutters are dumping water – I’ll connect downspouts into the French drain system via solid pipe so roof water bypasses the yard entirely.

- Permeable vs. Solid Sections: Sometimes parts of the run we use perforated pipe (to collect water) and other parts solid pipe (to carry it quickly under something or to prevent losing water where we don’t want it). For instance, if routing under a driveway, we use solid pipe there. Or if passing by a tree, maybe solid so we don’t water the tree’s roots.

The upshot: French drains aren’t one-size-fits-all. Designing them for our local conditions ensures they actually work and solve the problem at hand. A well-designed system can mean the difference between “yard is bone dry after a storm” and “hmm, it helped a bit but some water still sitting.” As a pro, I take pride in tailoring each install – factoring soil type, elevation, water source, and discharge options. When done right, a French drain in coastal NC can handle even the heavy rains and keep doing its job for many years.

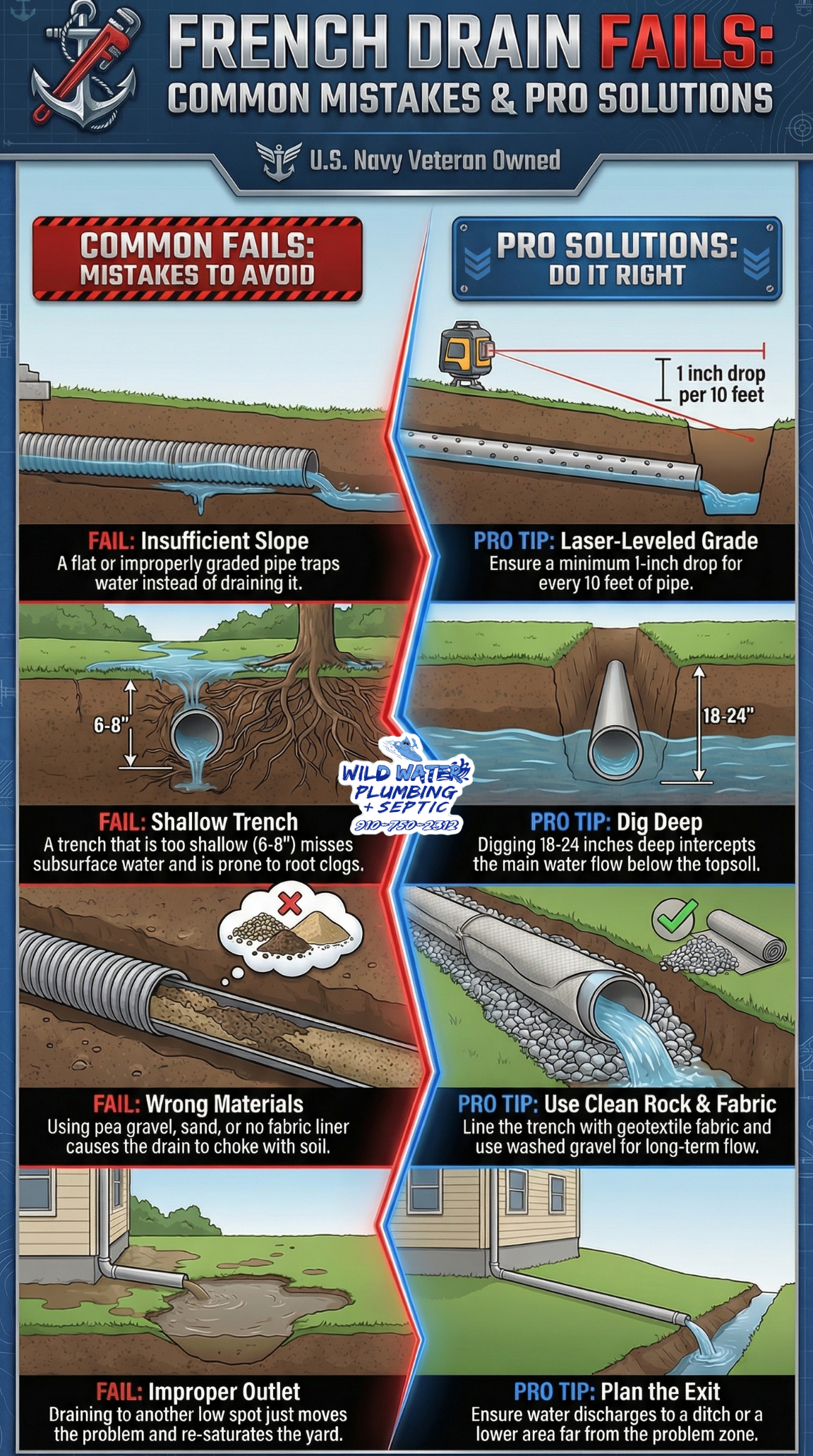

3.4 Proper Installation or “Don’t Do It Wrong”

I can’t talk about French drains without warning about the pitfalls. I get called all the time to look at French drains that homeowners or less-experienced contractors installed which don’t work. The idea is simple, but execution matters. Here are common mistakes and why proper installation is non-negotiable:

- Insufficient Slope (Flat Pipe): If the pipe isn’t graded correctly, water will sit in it – effectively, you’ve installed an underground pond. I’ve seen drains where the pipe was level or even had a negative slope (going uphill at one point). Water doesn’t defy gravity. We always use laser levels to ensure a continuous fall. The rule: at least 1 inch drop per 10 feet of run, more if possible. If your yard is truly flat, we might have to engineer a solution (like an endpoint sump pump). An almost-flat French drain is a failure waiting to happen.

- Trench Not Deep Enough: This is a biggie. If you put a French drain too shallow, you might just be catching surface water and missing the subsurface flow. Or you might not be below the root zone, so eventually roots clog it (especially if near trees). Also, a shallow pipe is more likely to be cut by future landscaping. We aim to put the pipe deep enough to intercept the main water flow – often that’s below the topsoil/clay interface. Depth also helps provide a cooling effect that draws water (think of it like a drain field in reverse). Many DIY drains are only 6-8 inches deep with a bit of gravel, which is not sufficient for serious issues. We typically go 18-24 inches deep or more as needed.

- Using the Wrong Gravel or No Fabric: A surprisingly common mistake is using cheap pea gravel or stone dust or other material that actually compacts or holds water. I’ve seen one drain filled with sand (someone thought it would absorb more – nope, it just became a sand trench). Clean, washed rock is the only way – it must allow easy flow. Also, not using geotextile fabric to line the trench is asking for clogs. Soil will migrate into the rocks over time and fill the voids. The fabric is what keeps your French drain working 5, 10, 20 years later. Yes, it’s an extra step and material cost, but it’s critical. Whenever I uncover a failing old drain, 9 times out of 10 there was no fabric and it’s completely choked with dirt.

- Improper Outlet / Nowhere to Go: Sometimes the installation is fine but the water has nowhere good to go – like draining to another low spot that floods. I recall one case: a guy installed a French drain that dumped out… right into his neighbor’s yard! (The neighbor was not pleased, and water ended up coming back anyway.) Or people will daylight a pipe at a point that is still within the flat yard, so it just seeps out and re-saturates the area. Designing a proper outlet (with maybe a pop-up emitter or a tie-in to a ditch) is crucial. We also ensure the outlet won’t become blocked – for instance, no one wants the end of their pipe to be underwater in a ditch constantly (then the pipe can’t drain). Sometimes we might build a small swale or mini-berm to guide the discharged water further away.

- Too Close to Septic or Foundations: Placement errors can cause new problems. A French drain too near a septic drain field could inadvertently start drawing septic effluent (yikes). We maintain clearances and usually stay downhill of septic components unless we are intentionally doing a curtain drain uphill. Near foundations, if you install a French drain improperly, you could undermine footings (like digging too close or too deep without shoring, causing soil collapse under the footing). Professional installers know how to avoid that, often by keeping some distance or by not going below the adjacent house’s footing level. Also, any time we’re near utilities, we get them located – nicking a buried power line or gas line is obviously a huge risk in DIY digs.

- Undersizing for Volume: Use a pipe large enough and aggregate sufficient for the expected water volume. Occasionally I see someone used a 2-inch pipe or just a little slotted flex-tube surrounded by a bit of gravel in a sock (those prefab drains) – those can work for minor issues, but for serious drainage, I prefer rigid 4” pipe with lots of gravel. It can handle large volumes of water. We had a project in North Topsail where basically half the yard’s water was being funneled – we used dual 4” pipes in one trench to increase capacity, because a single might have been overwhelmed in a downpour.

When properly installed, a French drain should be out-of-sight, out-of-mind – quietly doing its job for decades. It’s one of those things you forget is even there… until you realize that area of the yard hasn’t flooded since. I often get follow-up calls from customers after big rains, like, “Wow, I can’t believe how well that worked.” That makes my day, every time.

However, I’ll be honest: when installed poorly, a French drain can be a frustrating waste of money. I hate to see people spend on a fix that doesn’t fix. That’s why I emphasize doing it right or not at all. For many of you reading this in Onslow or nearby counties, you likely need some drainage solution. It could be a French drain, grading, or another method each home is different. But if a French drain is the ticket, make sure it’s done correctly, or consult a professional (like me or someone with experience).

With that, I’ll wrap up the how/why of French drains. You can tell I’m passionate about these because I’ve seen the transformation they bring: from soggy and suffering property to dry and thriving property. It’s a relatively small construction project with a very large payoff in our environment.

Data Table: Coastal North Carolina Drainage Issues and French Drain Solutions

| County | Geographic or Soil Characteristics | Specific Localities Mentioned | Drainage Challenges | Primary Risks to Property | Recommended French Drain Design Features |

| Onslow | Clay soils and dense subsoil (inland); sandy soil with high water table (coastal); flat terrain. | Jacksonville, Holly Ridge, Swansboro, Richlands, North Topsail Beach, Surf City, Sneads Ferry, Half Moon, Pumpkin Center, Haws Run, Back Swamp, Verona, Midway Park, Piney Green, Dixon, Folkstone, Petersburg. | Poor water absorption in clay; rapid soil saturation; high water table preventing infiltration; standing saltwater on barrier islands. | Septic system destruction; foundation cracks and structural damage; soil erosion; mold/mildew in crawlspaces; pest infestations. | Gravel-filled trench with 4-inch perforated PVC/HDPE pipe (holes facing down); 1% minimum slope; geotextile filter fabric wrap; proper discharge outlet; possible sump pump. |

| Pender | Coastal barrier islands and low-lying mainland; flat inland farmland with clay-rich soil. | Burgaw, Hampstead, Surf City, Topsail Beach, Atkinson, Watha, Rocky Point, Currie, Willard, Scotts Hill, Sloop Point, Yamacraw, Charity, Montague, Register, St. Helena. | Storm surges; high water table near marshes; river/creek flooding; slow drainage due to flat, compacted soil. | Saturated septic drain fields; foundation settlement; property value loss; long-term soggy yards preventing land use. | Strategic placement upslope of septic fields; use of laser levels for continuous fall in flat terrain; 3/4-inch washed gravel stone for flow space. |

| Carteret | Surrounded by Atlantic Ocean and Bogue Sound; built on or near marshland; high water table. | Morehead City, Beaufort, Newport, Cape Carteret, Cedar Point, Peletier. | Tidal flooding in yards and ditches; high tide preventing rainwater discharge; septic saturation from rising groundwater. | Septic failure on marginal land; saltwater damage to landscapes; foundation erosion; crawlspace humidity and wood rot. | Installation between house and marsh edge; one-way check valves on outlets to prevent tidal backflow; perforated pipe wrapped in filter fabric to prevent silt clogging. |

| New Hanover | Highly developed urban areas; fill dirt over clay or water-logged peat; high percentage of impervious surfaces. | Wilmington, Carolina Beach, Kure Beach, Wrightsville Beach, Castle Hayne, Ogden, Porters Neck, Bayshore, Myrtle Grove, Murrayville, Kings Grant, Northchase, Silver Lake, Pine Valley, Wrightsboro, Skippers Corner, Sea Breeze. | Runoff from roads and driveways; flooding of low-lying subdivisions; high water table in beach communities; retention pond overflow. | Mold growth and indoor air quality issues; foundation damage from hydrostatic pressure; loss of home equity/property value. | Drains along back fence lines to catch neighbor runoff; connection of downspouts into solid pipes; 18-24 inch depth; rigid 4-inch pipe for large volumes. |

Let’s move on to some Frequently Asked Questions I often hear about drainage and French drains, to address any lingering curiosities you might have.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How do I know if my yard needs a French drain or some drainage solution?

A: Look for the telltale signs of poor drainage. If you routinely see standing water that lingers for more than a few hours after rain, or areas of your yard that stay spongy and muddy for days, that’s a big clue. Also, any of the symptoms I listed earlier: puddles near your foundation, a persistently soggy area over your septic drain field, water pooling in low spots, moldy crawlspace smells, or interior drains gurgling during wet weather – those all suggest your property isn’t draining well on its own. In coastal NC, even if water eventually recedes, prolonged soil saturation can be harmful. A French drain is typically needed when simple surface grading isn’t enough to fix the problem or when you need to protect specific features (like diverting water around a septic field or away from a slab). If you’re unsure, a professional assessment can determine whether a French drain or another solution (such as re-grading, swales, or adding gutters) is best. But generally, if you have “problem puddles” or water intrusion issues, you would likely benefit from a French drain to provide an escape route for that water.

Q2: Will a French drain completely resolve my septic system issues?

A: A French drain can significantly alleviate the external water pressure on your septic system by keeping rain and groundwater away from the drain field, but it’s not a magic wand for all septic problems. If your septic system is already failing due to age, damage, or years of neglect (e.g., never pumping the tank), you may have internal issues that a French drain alone can’t fix. However, if the main issue is seasonal flooding of the drain field or slow drainage after rains, then yes – a French drain (or curtain drain) upslope of the field can prevent oversaturation and often bring a struggling system back to normal function. I’ve installed drains for clients whose septic alarms tripped whenever it rained, and afterward the alarms stayed quiet because the drains kept the area drier. Keep in mind, a French drain addresses excess water – it doesn’t replace proper septic maintenance. You’ll still need to pump your tank on schedule and avoid things that clog your field. But by controlling drainage, you remove the most significant external threat to the septic. So in summary, for water-related septic woes, a French drain is often an excellent fix. For other septic issues (like roots in lines or broken baffles), you’d need those repaired separately.

Q3: Do French drains work even in completely flat yards or areas with a high water table?

A: Yes, but they may need some creative engineering. In a completely flat yard, we can still make a French drain work by creating a very gentle slope (even a few inches of drop can be enough over a long run) or by using auxiliary measures. Sometimes we incorporate a sump pump basin at the low point – water flows into it and then a pump lifts it to an outflow at a higher elevation (for example, pumping into the street gutter). Essentially, if gravity alone isn’t enough, we give gravity a boost. As for high water tables, French drains can lower the localized water table around them by providing a drain point. However, if the water table is at ground surface during wet periods, the French drain will be running full and might need to discharge to a ditch or pump as well. An example: parts of Wilmington near marshes have a water table ~1’ below grade. We installed a French drain there and ran the outlet to a tidal creek with a check valve – during low tide it drains the yard, during high tide it temporarily holds water but keeps it out of the yard. In extremely flat areas, a French drain is sometimes designed more as an underground reservoir (large gravel volume) to hold water until it slowly percolates. That can still be better than surface flooding. So, French drains can work in tough conditions, but they might be part of a combined solution (drain + pump, or drain + dry well). A professional will assess the specific scenario. Generally, we haven’t met a yard yet where we couldn’t improve drainage – it’s about tailoring the approach.

Q4: Can I install a French drain myself, or should I hire a professional?

A: If you’re fairly handy, have the right tools, and the drainage issue is fairly minor, you can DIY a French drain in a small area (like along one side of a house). However, there are several reasons to consider a professional for anything more involved:

- Proper Grading: As discussed, getting the slope right is crucial. Pros have levels/lasers to ensure precision. A DIY might accidentally create a low spot in the pipe and not realize it.

- Labor and Equipment: Digging a trench that’s, say, 50+ feet long and 2-3 feet deep is hard work. In our compacted soils or clay layers, it might be beyond a shovel job. We often use trenchers or mini-excavators. Also, dealing with several tons of gravel and backfill is non-trivial for one person.

- Knowledge of Layout: A pro will know how to avoid utilities (we call NC811 to mark lines), how to route around landscaping, and how to tie into existing drainage infrastructure legally and effectively.

- Materials Selection: We use high-quality filter fabric, Schedule 40 or SDR35 perforated pipe (which won’t collapse), etc. A DIY might be tempted to use cheaper corrugated drain pipe – which can be okay short-term but often clogs or collapses later. We also know to add cleanouts (access points) if the run is long, so it can be serviced in future if needed.

- Experience: There’s something to be said for having done this many times. We recognize patterns – like “oh, the water is actually coming from that neighbor’s yard, so we need to start the drain higher” or “this low spot might be better fixed with a catch basin.” A pro might save you from doing the wrong fix.

That said, if you do want to DIY, do your homework: ensure you have a good slope, use fabric and proper gravel, keep it well away from your septic field, and plan a good outlet. Many Cooperative Extension services or online resources (including this guide!) offer guidelines. I’d estimate that simple projects (like 20’ drain along a driveway to stop puddles) are fine for DIY. Bigger projects (encircling a house or spanning a yard) – consider bringing in experts. The cost of a poorly done drain is not just wasted effort, but potentially continued water damage. Often I get called and the homeowner says, “I tried doing it myself and it helped a little, but not enough.” We come in and tweak or redo portions. If you value your time and want a long-term solution, hiring a professional is usually worth it. Plus, we often offer warranties on our work.

Q5: How much does it cost to install a French drain in this area?

A: Costs can vary widely depending on the scope, but I can give general ideas. For a standard residential French drain of, say, 50-100 feet length, expect somewhere in the ballpark of a couple thousand dollars when done professionally. Many installations in our area end up in the $1,500 to $5,000 range. Simpler, shorter drains (like a 20-foot tied into a gutter downspout problem area) might be on the lower end or even below $1k if very straightforward. Larger projects – for instance, wrapping around an entire house or multiple connection points – can go higher. If a sump pump is involved or significant restoration (like re-sodding a lot of lawn) is needed, that adds cost too. As a reference, waterproofing companies quote anywhere from $25 to $50 per linear foot of drain installed, but that can include other things. Our local market (Onslow/Pender counties) tends to be reasonable on pricing due to competition and our sandy soil being easier to dig than rock.

One thing I emphasize: compared to the cost of the damage water can do, a French drain is relatively cheap. Think, a foundation repair might be $10k+, septic replacement $5-10k, mold remediation $3-5k, property value loss $10k+, etc. Spending a few thousand on drainage could prevent those. Also, a properly done drain is a one-time cost that adds peace of mind every time it rains. When budgeting, also factor maintenance (though minimal) – e.g., every few years you might flush the drain or clear the outlet, but that’s minor.

I always offer homeowners an estimate and explain the cost breakdown (materials, labor, etc.). We try to work within budgets by perhaps tackling the worst area first if needed. Keep in mind, if you get quotes, ensure it’s for a comprehensive job (with fabric, proper depth, etc.) – a dirt-cheap quote may cut corners which can cost more later. It’s like the old saying: “You get what you pay for.” With drainage, doing it right might cost a bit more up front, but it’s worth it.

Q6: Do French drains require maintenance?

A: Very little, actually – which is the beauty of them. A well-installed French drain is largely set-and-forget. There are a few simple things to prolong its effectiveness:

- Keep the outlet clear: Wherever the pipe exits, make sure it doesn’t get blocked by debris, mulch, or overgrown grass. If it outlets to a ditch, keep that ditch cleaned so the pipe end isn’t submerged in sediment. I advise homeowners to check the outlet seasonally (especially after big storms) to ensure water can freely flow.

- Avoid clog sources: Try not to dump soil, mulch, or lots of sand over the area where the drain is – a bit won’t hurt since we have fabric, but you don’t want to create a scenario where tons of fine material constantly washes in. Also, don’t plant water-hungry tree species (like willow or river birch) right next to a French drain – their roots could infiltrate seeking water. Normal grass or garden plants are fine.

- Flushing (if needed): Every few years, you can flush the drain with a garden hose via an inlet or cleanout, just to make sure there’s no sediment accumulation. If we install cleanouts (which are small vertical pipes with caps connected to the drain line at strategic points), you can open those and run water in to flush, or even use a drain snake to clear any minor obstructions. Many drains never need this for a decade or more, but it’s an option.

- Surface grading upkeep: Ensure the surface above still drains toward the French drain collection zone. For example, if someone inadvertently regrades the yard later or adds a raised garden that blocks water from getting to the drain, that could reduce effectiveness. So maintain general slope toward the drain as initially intended.

In general, French drains are very low-maintenance. They don’t have mechanical parts (unless there’s a pump) and if protected with fabric, they shouldn’t clog easily. Contrast that with something like gutter downspouts – those you have to clean regularly. A French drain is quietly underground, doing its thing. I’ve seen 20-year-old drains still working great. If a problem does arise (like tree roots or an accidental cut through the pipe from other yard work), it can be fixed by repairing that section. But again, those are infrequent. Think of a French drain like a buried gutter for your yard – and gutters only need occasional cleaning. Same idea here.

Q7: Where does the water go after a French drain collects it?

A: This is important to plan – the water has to go somewhere harmless. Options include:

- Storm sewers or Street Gutters: In many subdivisions, we can discharge the water through a pop-up emitter in the lawn that flows overland into the street, or directly into a storm inlet if available (with city approval). Once it’s in the municipal system, it’s their problem (and usually they can handle it).

- Drainage Ditch or Swale: In rural parts of Onslow/Pender, most properties have a ditch along the road or property line. We often run the outlet to that ditch. The ditch then carries water to a creek or retention area. We try to outlet on your property or at a defined easement – you generally can’t legally dump water on a neighbor’s land (surface water laws can be prickly). So ditches are great natural endpoints.

- Dry Well or Infiltration Pit: If there’s really nowhere to send it horizontally, we may send it down vertically. A dry well is basically a big hole filled with stone (or a plastic chamber) that holds water and lets it slowly soak into the ground. This works best in sandy soils or where the volume isn’t huge. It’s like giving the water a deep underground storage so it’s not pooling on the surface.

- Retention Pond or Low Woods: Some properties border a woodline or pond; if allowed, we can discharge water there where a little extra won’t matter. Always respecting that we don’t want to create erosion or swamp someone else’s land.

- Pump to a Higher Outlet: As mentioned, if needed we use a sump pump system to lift water to one of the above (like up to the street level from a backyard).

In designing your French drain, I’ll always explain “We’re collecting the water here and it will exit there.” You should know that plan. Sometimes customers ask, “Won’t that just move the problem to [the outlet]?” We ensure the outlet is a place that can handle water – e.g., a city storm drain, a drainage easement, etc., which are designed for it. In fact, many neighborhoods require homeowners to not impede natural drainage; connecting to proper outfalls is being a good neighbor and citizen. And don’t worry – a properly working French drain doesn’t “store” water, it moves it. So you’re not exacerbating mosquito issues at the outlet (since ideally it flows and dissipates). In short, the water goes to a safe place where it won’t harm structures or septic systems – that’s either a designated drainage infrastructure or an area far enough away and low enough to percolate without causing harm.

These are some of the most common questions I field. If you have other curiosities, by all means ask a local expert or give me a shout. The key takeaway from this FAQ section is: drainage issues are solvable, and there are proven methods (like French drains) to solve them. It’s normal to have questions, and as a professional I love educating homeowners on how and why these solutions work.

Conclusion

Living in coastal North Carolina – whether it’s Onslow, Pender, Carteret, New Hanover, or nearby – means learning to coexist with water. We get abundant rain, occasional hurricanes, a high water table, and flat land, all of which can conspire to give our yards and homes a real soaking. But as we’ve explored, you don’t have to “live with” a swampy yard or a failing septic system or a musty, moldy crawlspace. There are concrete steps (pun intended) you can take to protect your property value, your home’s structure, and your family’s health from poor drainage.